Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, later known as Louis Napoleon and then Napoleon III, was born in Paris on the night of 19–20 April 1808.

Family

His father was Louis Bonaparte, the younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, who made Louis the king of Holland from 1806 until 1810. His mother was Hortense de Beauharnais, the only daughter of Napoleon's wife Joséphine by her first marriage to Alexandre de Beauharnais.

Charles-Louis was baptized at the Palace of Fontainebleau on 5 November 1810, with Emperor Napoleon serving as his godfather and Empress Marie-Louise as his godmother. His father stayed away, once again separated from Hortense. At the age of seven, Louis Napoleon visited his uncle at the Tuileries Palace in Paris. Napoleon held him up to the window to see the soldiers parading in the courtyard of the Carousel below. He last saw his uncle with the family at the Château de Malmaison, shortly before Napoleon departed for the Battle of Waterloo.

Education

When Louis Napoleon was fifteen, his mother Hortense moved to Rome, where the Bonapartes had a villa. He passed his time learning Italian, exploring the ancient ruins and learning the arts of seduction and romantic affairs, which he used often in his later life. He became friends with the French Ambassador, François-René Chateaubriand, the father of romanticism in French literature, with whom he remained in contact for many years. He was reunited with his older brother Napoléon-Louis; together they became involved with the Carbonari, secret revolutionary societies fighting Austria's domination of Northern Italy.

In the spring of 1831, when he was twenty-three, the Austrian and papal governments launched an offensive against the Carbonari. The two brothers, wanted by the police, were forced to flee. During their flight, Napoléon-Louis contracted measles. He died in his brother's arms on 17 March 1831.

Hortense joined her son and together they evaded the police and Austrian army and finally reached the French border.

Hortense and Louis Napoleon traveled incognito to Paris, where the old regime of King Charles X had just fallen and been replaced by the more liberal regime of King Louis Philippe, the sole monarch of the July Monarchy. They arrived in Paris on 23 April 1831, and took up residence under the name "Hamilton" in the Hotel du Holland on Place Vendôme. Hortense wrote an appeal to the King, asking to stay in France, and Louis Napoleon offered to volunteer as an ordinary soldier in the French Army. The new King agreed to meet secretly with Hortense; Louis Napoleon had a fever and did not join them.

The King finally agreed that Hortense and Louis Napoleon could stay in Paris as long as their stay was brief and incognito. Louis-Napoleon was told that he could join the French Army if he would simply change his name, something he indignantly refused to do. Hortense and Louis Napoleon remained

in Paris until 5 May, the tenth anniversary of the death of Napoleon Bonaparte. The presence of Hortense and Louis Napoleon in the hotel had become known, and a public demonstration of mourning for the Emperor took place on Place Vendôme in front of their hotel. The same day, Hortense and

Louis Napoleon were ordered to leave Paris. They went to Britain briefly, and then back into exile in Switzerland.

A turbulent path

Ever since the fall of Napoleon in 1815, a Bonapartist movement had existed in France, hoping to return a Bonaparte to the throne. According to the law of succession established by Napoleon I, the claim passed first to his own son, declared "King of Rome" at birth by his father. This heir, known by Bonapartists as Napoleon II, was living in virtual imprisonment at the court of Vienna under the title Duke of Reichstadt.

Next in line was Napoleon I's eldest brother Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844), followed by Louis Bonaparte (1778–1846), but neither Joseph nor Louis had any interest in re-entering public life.

When the Duke of Reichstadt died in 1832, Charles-Louis Napoleon became the de facto heir of the dynasty and the leader of the Bonapartist cause. In exile with his mother in Switzerland, he enrolled in the Swiss Army, trained to become an officer, and wrote a manual of artillery (his uncle Napoleon had

become famous as an artillery officer).

Louis Napoleon also began writing about his political philosophy—for as the early twentieth century English historian H. A. L. Fisher suggested, "the programme of the Empire was not the improvisation of a vulgar adventurer" but the result of deep reflection on the Napoleonic political philosophy and on how to adjust it to the changed domestic and international scenes.

He published his Rêveries politiques or "political dreams" in 1833 at the age of 25, followed in 1834 by Considérations politiques et militaires sur la Suisse ("Political and military considerations about Switzerland"), followed in 1839 by Les Idées napoléoniennes ("Napoleonic Ideas"), a compendium of his political ideas which was published in three editions and eventually translated into six languages. He based his doctrine upon two ideas: universal suffrage and the primacy of the national interest. He called for a "monarchy which procures the advantages of the Republic without the inconveniences", a regime "

strong without despotism, free without anarchy, independent without conquest".

He began to plan a coup against King Louis-Philippe. He planned for his uprising to begin in Strasbourg. The colonel of a regiment was brought over to the cause. On 29 October 1836, Louis Napoleon arrived in Strasbourg, in the uniform of an artillery officer; he rallied the regiment to his side. The prefecture was seized, and the prefect arrested. Unfortunately for Louis-Napoleon, the general commanding the garrison escaped and called in a loyal regiment, which surrounded the mutineers. The mutineers surrendered and Louis-Napoleon fled back to Switzerland.

King Louis Philippe of the French

King Louis-Philippe demanded that the Swiss government return Louis Napoleon to France, but the Swiss pointed out that he was a Swiss soldier and citizen, and refused to hand him over. Louis-Philippe responded by sending an army to the Swiss border. Louis Napoleon thanked his Swiss hosts, and voluntarily left the country. The other mutineers were put on trial in Alsace, and were all acquitted.

Louis Napoleon traveled first to London, then to Brazil, and then to New York. He moved into a hotel, where he met the elite of New York society and the writer Washington Irving. While he was traveling to see more of the United States, he received word that his mother was very ill. He hurried as quickly as he could back to Switzerland. He reached Arenenberg in time to be with his mother on 5 August 1837, when she died. She was finally buried in Rueil, in France, next to her mother, on 11 January 1838, but

Louis Napoleon could not attend, because he was not allowed into France.

Washington Irving

Louis Napoleon returned to London for a new period of exile in October 1838. He had inherited a large fortune from his mother and took a house with seventeen servants and several of his old friends and fellow conspirators. He was received by London society and met the political and scientific leaders of the day, including Benjamin Disraeli and Michael Faraday. He also did considerable research into

the economy of Britain. He strolled in Hyde Park, which he later used as a model when he created the Bois de Boulogne in Paris.

London

Living in the comfort of London, he had not given up the dream of returning to France to seize power. In the summer of 1840 he bought weapons and uniforms and had proclamations printed, gathered a contingent of about sixty armed men, hired a ship called the Edinburgh-Castle, and on 6 August 1840,

sailed across the Channel to the port of Boulogne. The attempted coup turned into an even greater fiasco than the Strasbourg mutiny. The mutineers were stopped by the customs agents, the soldiers of the garrison refused to join, the mutineers were surrounded on the beach, one was killed and the others

arrested. Both the British and French press heaped ridicule on Louis-Napoleon and his plot. The newspaper Le Journal des Débats wrote, "this surpasses comedy.

In prison & a book

While in prison, he wrote poems, political essays, and articles on diverse topics. He contributed articles to regional newspapers and magazines in towns all over France, becoming quite well known as a writer. His most famous book was L'extinction du pauperisme (1844), a study of the causes of poverty

in the French industrial working class, with proposals to eliminate it. His conclusion: "The working class has nothing, it is necessary to give them ownership. They have no other wealth than their own labor, it is necessary to give them work that will benefit all....they are without organization and without connections, without rights and without a future; it is necessary to give them rights and a future and to raise them in their own eyes by association, education, and discipline."

He was busy in prison, but also unhappy and impatient. He was aware that the popularity of Napoleon Bonaparte was steadily increasing in France; the Emperor was the subject of heroic poems, books

and plays. Huge crowds had gathered in Paris on 15 December 1840 when the remains of Napoleon Bonaparte were returned with great ceremony to Paris and handed over to Louis Napoleon's old enemy,

King Louis-Philippe, while Louis Napoleon could only read about it in prison. On 25 May 1846, with the assistance of his doctor and other friends on the outside, he disguised himself as a laborer carrying lumber, and walked out of the prison. His enemies later derisively called him "Badinguet", the name of the laborer whose identity he had assumed. A carriage was waiting to take him to the coast and then by boat to England. A month after his escape, his father Louis died, making Louis Napoleon the clear heir to the Bonaparte dynasty.

Back in Great Britain

He quickly resumed his place in British society. He lived on King Street in St James's, London, went to the theatre and hunted, renewed his acquaintance with Benjamin Disraeli, and met Charles Dickens.

He went back to his studies at the British Museum. He had an affair with the actress Rachel, the most famous French actress of the period, during her tours to Britain.

More important for his future career, he had an affair with the wealthy heiress Harriet Howard (1823–1865). They met in 1846, soon after his return to Britain.

Harriet Howard

They began to live together, she took in his two illegitimate children and raised them with her own son, and she provided financing for his political plans so that, when the moment came, he could return to France

In February 1848, Louis Napoleon learned that the French Revolution of 1848 had broken out; Louis Philippe, faced with opposition within his government and army, abdicated. Believing that his time had finally come, he set out for Paris on 27 February, departing England on the same day that Louis-Philippe left France for his own exile in England.

When he arrived in Paris, he found that the Second Republic had been declared, led by a Provisional Government headed by a Commission led by Alphonse de Lamartine, and that different factions of republicans, from conservatives to those on the far left, were competing for power.

He wrote to Lamartine announcing his arrival, saying that he "was without any other ambition than that of serving my country". Lamartine wrote back politely but firmly, asking Louis-Napoleon to leave Paris "until the city is more calm, and not before the elections for the National Assembly". His close advisors

urged him to stay and try to take power, but he wanted to show his prudence and loyalty to the Republic; while his advisors remained in Paris, he returned to London on 2 March 1848 and watched events from there.

Rise to power

He did not run in the first elections for the National Assembly, held in April 1848, but three members of the Bonaparte family, Jérôme Napoléon Bonaparte, Pierre Napoléon Bonaparte, and Lucien Murat were elected; the name Bonaparte still had political power.

In the next elections, on 4 June, where candidates could run in multiple departments, he was elected in four different departments; in Paris, he was among the top five candidates, just after the conservative leader Adolphe Thiers and Victor Hugo.

His followers were mostly on the left, from the peasantry and working class. His pamphlet on "The Extinction of Pauperism" was widely circulated in Paris, and his name was cheered with those of the socialist candidates Barbès and Louis Blanc.

The Moderate Republican leaders of the provisional government, Lamartine and Cavaignac, considered arresting him as a dangerous revolutionary, but once again he outmaneuvered them. He wrote to the President of the Provisional Government: "I believe I should wait to return to the heart of my country, so that my presence in France will not serve as a pretext to the enemies of the Republic."

In June 1848, the June Days Uprising broke out in Paris, led by the far left, against the conservative majority in the National Assembly. Hundreds of barricades appeared in the working-class neighborhoods. General Cavaignac, the leader of the army, first withdrew his soldiers from Paris to allow the insurgents to deploy their barricades, and then returned with overwhelming force to crush the uprising; from 24 to 26 June, there were battles in the streets of the working class districts of Paris. An estimated five thousand insurgents were killed at the barricades, fifteen thousand were arrested, and four thousand deported.

His absence from Paris meant that Louis Napoleon was not connected either with the uprising, or with the brutal repression that had followed. He was still in London on 17–18 September, when the elections for the National Assembly were held, but he was a candidate in thirteen departments. He was elected in fivedepartments; in Paris, he received 110,000 votes of the 247,000 cast, the highest number of votes of any candidate. He returned to Paris on 24 September, and this time he took his place in the National Assembly. In seven months, he had gone from a political exile in London to a highly visible place in the National Assembly, as the government finished the new Constitution and prepared for the first election ever of a President of the French Republic.

The elections were held on 10–11 December. Results were announced on 20 December. Louis Napoleon was widely expected to win, but the size of his victory surprised almost everyone.

He was imprisoned, however Napoleon III commuted his imprisonment to an exile and he was allowed back into France in 1862

He also made his first venture into foreign policy, in Italy, where as a youth he had joined in the patriotic uprising against the Austrians. The previous government had sent an expeditionary force, which had been tasked and funded by the National Assembly to support the republican forces in Italy against the Austrians and against the Pope. Instead the force was secretly ordered to do the opposite, namely to enter Rome to help restore the temporal authority of Pope Pius IX, who had been overthrown by Italian republicans including Mazzini and Garibaldi. The French troops came under fire from Garibaldi's soldiers. The Prince-President, without consulting his ministers, ordered his soldiers to fight if needed in support of the Pope. This was very popular with French Catholics, but infuriated the republicans, who supported the Roman Republic.

To please the radical republicans, he asked the Pope to introduce liberal reforms and the Code Napoleon to the Papal States. To gain support from the Catholics, he approved the Loi Falloux in 1851, which restored a greater role for the Catholic Church in the French educational system.

Elections were held for the National Assembly on 13–14 May 1849, only a few months after Louis Napoleon had become president, and were largely won by a coalition of conservative republicans—which Catholics and monarchists called "The Party of Order"— led by Adolphe Thiers. The socialists and "red" republicans, led by Ledru-Rollin and Raspail, also did well, winning two hundred seats. The moderate republicans, in the middle, did very badly, taking just 70–80 seats. The Party of Order had a clear majority, enough to block any initiatives of Louis Napoleon.

On 11 June 1849 the socialists and radical republicans made an attempt to seize power. Ledru-Rollin, from his headquarters in the Conservatory of Arts and Professions, declared that Louis Napoleon was no longer President and called for a general uprising.

A few barricades appeared in the working-class neighborhoods of Paris. Louis Napoleon acted swiftly, and the uprising was short-lived. Paris was declared in a state of siege, the headquarters of the uprising

was surrounded, and the leaders arrested. Ledru-Rollin fled to England, Raspail was arrested and sent to prison, the republican clubs were closed, and their newspapers closed down.

The National Assembly, now without the left republicans and determined to keep them out forever, proposed a new election law that placed restrictions on universal male suffrage, imposing a three-year residency requirement.

Louis Napoleon broke with the Assembly and the conservative ministers opposing his projects in favour of the dispossessed. He secured the support of the army, toured the country making populist speeches that condemned the Assembly, and presented himself as the protector of universal male suffrage. He demanded that the law be changed, but his proposal was defeated in the Assembly by a vote of 355 to 348.

According to the Constitution of 1848, he had to step down at the end of his term, so Louis Napoleon sought a constitutional amendment to allow him to succeed himself, arguing that four years were not enough to fully implement his political and economic program. He toured the country and gained

support from many of the regional governments and many within the Assembly. The vote in July 1851 was 446 to 278 in favor of changing the law and allowing him to run again, but this was short of the two-thirds majority needed to amend the constitution.

Louis Napoleon believed that he was supported by the people, and he decided to retain power by other means. His half-brother Morny and a few close advisors quietly began to organise a coup d'état. They included minister of war Jacques Leroy de Saint Arnaud, as well as officers from the French Army in North Africa, to provide military backing for the coup.

On the night of 1–2 December, Saint Arnaud's soldiers quietly occupied the national printing office, the Palais Bourbon, newspaper offices, and the strategic points in the city. In the morning, Parisians found posters around the city announcing the dissolution of the National Assembly, the restoration of universal suffrage, new elections, and a state of siege in Paris and the surrounding departments.

Sixteen members of the National Assembly were arrested in their homes. When about 220 deputies of the moderate right gathered at the city hall of the 10th arrondissement, they were also arrested.

On 3 December, writer Victor Hugo and a few other republicans tried to organize an opposition to the coup. A few barricades appeared, and about 1,000 insurgents came out in the streets, but the army moved in force with 30,000 troops and the uprisings were swiftly crushed, with the killing of an estimated 300 to 400 opponents of the coup.There were also small uprisings in the more militant red republican towns in the south and center of France, but these were all put down by 10 December.

Louis Napoleon's goal was to move from despotism to parliamentary government without a revolution, but instead he was a moderate increasingly trapped between the royalist and radical extremes.The 1851 referendum also gave Louis-Napoleon a mandate to amend the constitution. Work began on the new document in 1852. It was officially prepared by a committee of eighty experts, but was actually drafted by a small group of the Prince-President's inner circle.

Louis Napoleon's government imposed new authoritarian measures to control dissent and reduce the power of the opposition. One of his first acts was to settle scores with his old enemy, King Louis-Philippe, who had sent him to prison for life, and who had died in 1850. A decree on 23 January 1852 forbade the late King's family to own property in France and annulled the inheritance he had given to his children before he became King.

The National Guard, whose members had sometimes joined anti-government demonstrations, was re-organized and largely used only in parades. Government officials were required to wear uniforms at official formal occasions. The Minister of Education was given the power to dismiss professors at the universities and review the content of their courses. Students at the universities were forbidden to wear beards, seen as a symbol of republicanism.

Paris

When Napoleon returned to Paris the city was decorated with large arches, with banners proclaiming "To Napoleon III, emperor". In response to officially inspired requests for the return of the empire, the Senate scheduled another referendum for 21–22 November 1852 on whether to make Napoleon emperor. After an implausible 97 percent voted in favour (7,824,129 votes for and 253,159 against, with two million abstentions), on 2 December 1852—exactly one year after the coup—the Second Republic was officially ended, replaced by the Second French Empire.

Prince-President Louis Napoleon Bonaparte became Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. His regnal name treats Napoleon II, who never actually ruled, as a true Emperor (he had been briefly recognized as emperor from 22 June to 7 July 1815). The 1852 constitution was retained; it concentrated so much

power in Napoleon's hands that the only substantive change was to replace the word "president" with the word "emperor"

One of the first priorities of Napoleon III was the modernisation of the French economy, which had fallen far behind that of the United Kingdom and some of the German states. Political economics had long been a passion of the Emperor. While in Britain, he had visited factories and railway yards; in prison, he had studied and written about the sugar industry and policies to reduce poverty.

He also opened up French markets to foreign goods, such as railway tracks from England, forcing French industry to become more efficient and more competitive. The period was favorable for industrial expansion. The gold rushes in California and Australia increased the European money supply.

In the early years of the Empire, the economy also benefited from the coming of age of those born during the baby boom of the Restoration period. The steady rise of prices caused by the increase

of the money supply encouraged company promotion and investment of capital.

Beginning in 1852, Napoleon III encouraged the creation of new banks, such as Crédit Mobilier, which sold shares to the public and provided loans to both private industry and to the government.

Crédit Lyonnais was founded in 1863 and Société Générale in 1864. These banks provided the funding for Napoleon III's major projects, from railway and canals to the rebuilding of Paris.

In 1851, France had only 3,500 kilometers of railway, compared with 10,000 kilometers in England and 800 kilometers in Belgium, a country one-twentieth the size of France.

Within days of the coup d'état of 1851, Napoleon III's Minister of Public Works launched a project to build a railway line around Paris, connecting the different independent lines coming into Paris from

around the country. The government provided guarantees for loans to build new lines and urged railway companies to consolidate. There were 18 railway companies in 1848 and six at the end of

the Empire. By 1870, France had 20,000 kilometers of railway linked to the French ports and to the railway systems of the neighbouring countries that carried over 100 million passengers a year and transported the products of France's new steel mills, mines and factories.

Paris

Enormous public works projects reconstructed the center of Paris. Here, work to extend the Rue de Rivoli continues at night by electric light (1854). New shipping lines were created and ports rebuilt in Marseille and Le Havre, which connected France by sea to the US, Latin America, North Africa and the

Far East. During the Empire, the number of steamships tripled, and by 1870, France possessed the second-largest maritime fleet in the world after England.

Napoleon III backed the greatest maritime project of the age, the construction of the Suez Canal between 1859 and 1869. The canal project was funded by shares on the Paris stock market and led by a former French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps. It was opened by the Empress Eugénie with a performance of Verdi's opera Aida.

The rebuilding of central Paris also encouraged commercial expansion and innovation. The first department store, Bon Marché, opened in Paris in 1852 in a modest building and expanded rapidly, its income increasing from 450,000 francs a year to 20 million. Its founder, Aristide Boucicaut, commissioned a new glass and iron building designed by Louis-Charles Boileau and Gustave Eiffel

that opened in 1869 and became the model for the modern department store. Other department stores quickly appeared: Au Printemps in 1865 and La Samaritaine in 1870. They were soon imitated around the world.

Napoleon III's program also included reclaiming farmland and reforestation. One such project in the Gironde department drained and reforested 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 square miles) of moorland, creating the Landes forest, the largest maritime pine forest in Europe.

Camille Pissarro, Avenue de l'Opéra, one of the new boulevards created by Napoleon III. The new buildings on the boulevards were required to be all of the same height and same basic facade design, and all faced with cream coloured stone, giving the city center its distinctive harmony.

Napoleon III began his regime by launching a series of enormous public works projects in Paris, hiring tens of thousands of workers to improve the sanitation, water supply and traffic circulation of the city. To direct this task, he named a new prefect of the Seine department, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, and

gave him extraordinary powers to rebuild the center of the city. He installed a large map of Paris in a central position in his office, and he and Haussmann planned the new Paris.

To accommodate the growing population and those who would be forced from the center by the construction of new boulevards and squares, Napoleon III issued a decree in 1860 to annex eleven communes (municipalities) on the outskirts of Paris and increase the number of arrondissements (city boroughs) from twelve to twenty. Paris was thus enlarged to its modern boundaries with the exception of the two major city parks (Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes) that only became part of the

French capital in 1920.

For the duration of Napoleon III's reign and a decade afterwards, most of Paris was an enormous construction site. His hydraulic chief engineer, Eugène Belgrand, built a new aqueduct to bring clean water from the Vanne River in the Champagne region, and a new huge reservoir near the future Parc Montsouris. These two works increased the water supply of Paris from 87,000 to 400,000 cubic meters of water a day.

Hundreds of kilometers of pipes distributed the water throughout the city, and a second network, using the less-clean water from the Ourcq and the Seine, washed the streets and watered the new park and gardens. He completely rebuilt the Paris sewers and installed miles of pipes to distribute gas for thousands of new streetlights along the Paris streets.

Beginning in 1854, in the center of the city, Haussmann's workers tore down hundreds of old buildings and constructed new avenues to connect the central points of the city. Buildings along these avenues were required to be the same height, constructed in an architecturally similar style, and be faced with cream- coloured stone to create the signature look of Paris boulevards.

Haussmann

Napoleon III built two new railway stations: the Gare de Lyon (1855) and the Gare du Nord (1865). He completed Les Halles, the great cast iron and glass pavilioned produce market in the center of the city, and built a new municipal hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, in the place of crumbling medieval buildings on the

Ile de la Cité. The signature architectural landmark was the Paris Opera, the largest theater in the world, designed by Charles Garnier to crown the center of Napoleon III's new Paris.

Napoleon III's new parks were inspired by his memories of the parks in London, especially Hyde Park, where he had strolled and promenaded in a carriage while in exile; but he wanted to build on a much larger scale.

Working with Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, the engineer who headed the new Service of Promenades and Plantations, he laid out a plan for four major parks at the cardinal points of the compass around the city. Thousands of workers and gardeners began to dig lakes, build cascades, plant lawns, flowerbeds and trees, and construct chalets and grottoes.

Napoleon III transformed the Bois de Boulogne into a park (1852–58) to the west of Paris. To the east, he created the Bois de Vincennes (1860–65), and to the north, the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (1865–67).

The Parc Montsouris (1865–78) was created to the south.

In addition to building the four large parks, Napoleon had the city's older parks, including the Parc Monceau, formerly owned by the Orléans family, and the Jardin du Luxembourg, refurbished and replanted.

He also created some twenty small parks and gardens in the neighbourhoods as miniature versions of his large parks. Alphand termed these small parks "green and flowering salons". The intention of Napoleon's plan was to have one park in each of the eighty "quartiers" (neighbourhoods) of Paris, so that no one was more than a ten-minute walk from such a park. The parks were an immediate success with all classes of Parisian.

Soon after becoming emperor, Napoleon III began searching for a wife to give him an heir. He was still attached to his companion Harriet Howard, who attended receptions at the Élysée Palace and traveled around France with him. He quietly sent a diplomatic delegation to approach the family of Princess Carola of Vasa, the granddaughter of deposed King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden.

They declined because of his Catholic religion and the political uncertainty about his future, as did the family of Princess Adelheid of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, a niece of Queen Victoria.

Louis-Napoleon finally announced that he found the right woman: a Spaniard named Eugénie du Derje de Montijo, age 23, 20th Countess of Teba and 15th Marchioness of Ardales.

The daughter of the Count of Montijo, she received much of her education in Paris. Her beauty attracted Louis-Napoleon, who, as was his custom, tried to seduce her, but Eugénie told him to wait for marriage. The civil ceremony took place at Tuileries Palace on 22 January 1853, and a much grander ceremony was held a few days later at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. In 1856, Eugénie gave birth to a son and heir-apparent, Napoléon, Prince Imperial.

With an heir to the throne secured, Napoleon III resumed his "petites distractions" with other women. Eugénie faithfully performed the duties of an Empress, entertaining guests and accompanying the Emperor to balls, opera, and theatre. She traveled to Egypt to open the Suez Canal and officially

represented him whenever he traveled outside France.

Though a fervent Catholic and conservative on many other issues, she strongly advocated equality for women. She pressured the Ministry of National Education to give the first baccalaureate diploma to a woman and tried unsuccessfully to induce the Académie Française to elect the writer George Sand as its first female member.

Louis Napoleon has a historical reputation as a womanizer, yet he said: "It is usually the man who attacks. As for me, I defend myself, and I often capitulate."

He had many mistresses. During his reign, it was the task of Count Felix Bacciochi, his social secretary, to arrange for trysts and to procure women for the Emperor's favours.

His affairs were not trivial sideshows: they distracted him from governing, affected his relationship with the empress, and diminished him in the views of the other European courts.

Diplomacy & Foreign policy?

In foreign policy, Napoleon III aimed to reassert French influence in Europe and around the world as a supporter of popular sovereignty and nationalism.

In Europe, he allied himself with Britain and defeated Russia in the Crimean War (1854–56). French troops assisted Italian unification by fighting on the side of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

In return, France received Savoy and the county of Nice in 1860. Later, however, to appease fervent French Catholics, he sent soldiers to defend the residual Papal States against annexation by Italy.

At the beginning of his reign, he was also an advocate of a new "principle of nationalities" (principe des nationalités) that supported the creation of new states based on nationality, such as Italy, in place of the old multinational empires, such as the Habsburg monarchy (or Empire of Austria, known since 1867 as Austria-Hungary).

In this he was influenced by his uncle's policy as described in the Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène.

In all of his foreign policy ventures, he put the interests of France first. Napoleon III felt that new states created on the basis of national identity would become natural allies and partners of France.

From the start of his Empire, Napoleon III sought an alliance with Britain. He had lived there while in exile and saw Britain as a natural partner in the projects he wished to accomplish. An opportunity soon presented itself:

In early 1853, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia put pressure on the weak Ottoman government, demanding that the Ottoman Empire give Russia a protectorate over the Christian countries of the Balkans as well as control over Constantinople and the Dardanelles.

The Ottoman Empire, backed by Britain and France, refused Russia's demands, and a joint British-French fleet was sent to support the Ottoman Empire. When Russia refused to leave the Romanian

territories it had occupied, Britain and France declared war on 27 March 1854.

It took France and Britain six months to organize a full-scale military expedition to the Black Sea. The Anglo-French fleet landed thirty thousand French and twenty thousand British soldiers in the Crimea

on 14 September and began to lay siege to the major Russian port of Sevastopol. As the siege dragged on, the French and British armies were reinforced and troops from the Kingdom of Sardinia joined them, reaching a total of 140,000 soldiers, but they suffered terribly from epidemics of typhus, dysentery, and cholera.

During the 332 days of the siege, the French lost 95,000 soldiers, including 75,000 due to disease. The suffering of the army in the Crimea was carefully concealed from the French public by press censorship.

The death of Tsar Nicholas I on 2 March 1855 and his replacement by Alexander II changed the political equation. In September, after a massive bombardment, the Anglo-French army of fifty thousand men stormed the Russian positions, and the Russians were forced to evacuate Sevastopol. Alexander II sought a political solution, and negotiations were held in Paris in the new building of the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay, from 25 February to 8 April 1856.

The Crimean War added three new place names to Paris: Alma, named for the first French victory on the river of that name; Sevastopol; and Malakoff, named for a tower in the center of the Russian line captured by the French.

The war had two important diplomatic consequences: Alexander II became an ally of France, and Britain and France were reconciled. In April 1855, Napoleon III and Eugénie went to England and were received by the Queen; in turn, Victoria and Prince Albert visited Paris. Victoria was the first British monarch to do so in centuries.

The defeat of Russia and the alliance with Britain gave France increased authority and prestige in Europe. This was the first war between European powers since the close of the Napoleonic Wars

and the Congress of Vienna, marking a breakdown of the alliance system that had maintained peace for nearly half a century. The war also effectively ended the Concert of Europe and the Quadruple Alliance, or "Waterloo Coalition," that the other four powers (Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain) had established.

The Paris Peace Conference of 1856 represented a high-water mark for Napoleon's regime in foreign affairs. It encouraged Napoleon III to make an even bolder foreign policy venture in Italy.

Italian Campaign

On the evening of 14 January 1858, Napoleon and the Empress escaped an assassination attempt unharmed. A group of conspirators threw three bombs at the imperial carriage as it made its way to the opera. Eight members of the escort and bystanders were killed and over one hundred people injured.

The culprits were quickly arrested. The leader was an Italian nationalist, Felice Orsini, who was aided by a French surgeon Simon Bernard. They believed that if Napoleon III were killed, a republican revolt would immediately follow in France and the new republican government would help all Italian states win independence from Austria and achieve national unification. Bernard was in London at the time. Since he was a political exile, the Government of the United Kingdom refused to extradite him, but Orsini was tried, convicted and executed on 13 March 1858. The bombing focused the attention of France and particularly of Napoleon III, on the issue of Italian nationalism.

Part of Italy, particularly the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (officially the Kingdom of Sardinia), was independent, but central Italy was still ruled by the Pope (in this era, Pope Pius IX), while Venice, Lombardy and much of the north was ruled by Austria.

Other states were de jure independent (notably the Duchy of Parma or the Grand Duchy of Tuscany) but de facto fully under Austrian influence. Napoleon III had fought with the Italian patriots against the

Austrians when he was young and his sympathy was with them, but the Empress, most of his government and the Catholic Church in France supported the Pope and the existing governments.

The British Government was also hostile to the idea of promoting nationalism in Italy. Despite the opposition within his government and in his own palace, Napoleon III did all that he could to support the cause of Piedmont-Sardinia.

The King of Piedmont-Sardinia,

Victor Emmanuel II, was

invited to Paris in November 1855 and given the same royal

treatment as Queen Victoria.

In July 1858, Napoleon arranged a secret visit by Count Cavour. They agreed to join forces and drive the Austrians from Italy. In exchange, Napoleon III asked for Savoy (the ancestral land of the King of Piedmont-Sardinia) and the then bilingual County of Nice, which had been taken from France after Napoleon's fall in 1815 and given to Piedmont-Sardinia. Cavour protested that Nice was Italian,

but Napoleon responded that "these are secondary questions. There will be time later to discuss them."

Assured of the support of Napoleon III, Count Cavour began to prepare the army of Piedmont-Sardinia for war against Austria. Napoleon III looked for diplomatic support. He approached Lord Derby (the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) and his government; Britain was against the war, but agreed to remain neutral. Still facing strong opposition within his own government, Napoleon III offered to negotiate a diplomatic solution with the twenty-eight-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in the spring of 1858.

The Austrians demanded the disarmament of Piedmont-Sardinia first, and sent a fleet with thirty thousand soldiers to reinforce their garrisons in Italy.

Napoleon III responded on 26 January 1859 by signing a treaty of alliance with Piedmont-Sardinia. Napoleon promised to send two hundred thousand soldiers to help one hundred thousand soldiers from Piedmont-Sardinia to force the Austrians out of Northern Italy; in return, France would receive the County of Nice and Savoy provided that their populations would agree in a referendum.

It was the Emperor Franz Joseph, growing impatient, who finally unleashed the war.

On 23 April 1859, he sent an ultimatum to the government of Piedmont-Sardinia demanding that they stop their military preparations and disband their army.

On 26 April, Count Cavour rejected the demands, and on 27 April, the Austrian army invaded Piedmont.

War in Italy

Napoleon III, though he had very little military experience, decided to lead the French army in Italy himself. Part of the French army crossed over the Alps, while the other part, with the Emperor,

landed in Genoa on 18 May 1859. Fortunately for Napoleon and the Piedmontese, the commander of the Austrians, General Giulay, was not very aggressive.

His forces greatly outnumbered the Piedmontese army at Turin, but he hesitated, allowing the French and Piedmontese to unite their forces.

Napoleon III wisely left the fighting to his professional generals. The first great battle of the war, on 4 June 1859, was fought at the town of Magenta. It was long and bloody, and the French center was exhausted and nearly broken, but the battle was finally won by a timely attack on the Austrian flank by the soldiers of General MacMahon.

The Austrians had seven thousand men killed and five thousand captured, while the French forces had four thousand men killed. The battle was largely remembered because, soon after it was fought, patriotic chemists in France gave the name of the battle to their newly discovered bright purple chemical dye; the dye and the colour took the name magenta.

The rest of the Austrian army was able to escape while Napoleon III and King Victor Emmanuel made a triumphal entry on 10 June into the city of Milan, previously ruled by the Austrians. They were greeted by huge, jubilant crowds waving Italian and French flags.

The Austrians had been driven from Lombardy, but the army of General Giulay remained in the region of Venice. His army had been reinforced and numbered 130,000 men, roughly the same as the French and Piedmontese, though the Austrians were superior in artillery.

On 24 June, the second and decisive battle was fought at Solferino. This battle was even longer and bloodier than Magenta. In confused and often ill-directed fighting, there were approximately forty thousand casualties, including 11,500 French.

Napoleon III was horrified by the thousands of dead and wounded on the battlefield. He proposed an armistice to the Austrians, which was accepted on 8 July. A formal treaty ending the war was signed on 11 July 1859.

Count Cavour and the Piedmontese were bitterly disappointed by the abrupt end of the war. Lombardy had been freed, but Venetia (the Venice region) was still controlled by the Austrians, and the Pope was still the ruler of Rome and Central Italy. Cavour angrily resigned his post. Napoleon III returned to Paris on 17 July, and a huge parade and celebration were held on 14 August, in front of the Vendôme column, the symbol of the glory of Napoleon I. Napoleon III celebrated the day by granting a general amnesty to the political prisoners and exiles he had chased from France.

Carmillo Benso, Count Carvour

Did you know that his godparents were:

Napoleon I's sister Pauline, and her husband, Prince

Camillo Borghese,

after whom Camillo was named

In Italy, even without the French army, the process of Italian unification launched by Cavour and Napoleon III took on a momentum of its own. There were uprisings in central Italy and the Papal states, and Italian patriots, led by Garibaldi, invaded and took over Sicily, which would lead to the collapse

of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Napoleon III wrote to the Pope and suggested that he "make the sacrifice of your provinces in revolt and confide them to Victor Emmanuel". The Pope, furious, declared in a public address that Napoleon III was a "liar and a cheat".

Rome and the surrounding Latium region remained in Papal hands, and therefore did not immediately become the capital of the newly created Kingdom of Italy, and Venetia was still occupied by the Austrians, but the rest of Italy had come under the rule of Victor Emmanuel.

As Cavour had promised, Savoy and the county of Nice were annexed by France in 1860 after referendums, although it is disputed how fair they were. In Nice, 25,734 voted for union with France, just 260 against, but Italians still called for its return into the 20th century.

On 18 February 1861, the first Italian parliament met in Turin, and on 23 March, Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy. Count Cavour died a few weeks later, declaring that "Italy is made."

Napoleon's support for the Italian patriots and his confrontation with Pope Pius IX over who would govern Rome made him unpopular with fervent French Catholics, and even with Empress Eugénie, who was a fervent Catholic. To win over the French Catholics and his wife, he agreed to guarantee that Rome would remain under the Pope and independent from the rest of Italy, and agreed to keep French troops there.

The capital of Italy became Turin (in 1861) then Florence (in 1865), not Rome. However, in 1862, Garibaldi gathered an army to march on Rome, under the slogan, "Rome or death".

To avoid a confrontation between Garibaldi and the French soldiers, the Italian government sent its own soldiers to face them, arrested Garibaldi and put him in prison. Napoleon III sought, but was unable to find, a diplomatic solution that would allow him to withdraw French troops from Rome while

guaranteeing that the city would remain under Papal control.

Garibaldi

Garibaldi made another attempt to capture Rome in November 1867, but was defeated by the French and Papal troops near the town of Mentana on 3 November 1867.

The garrison of eight thousand French troops remained in Rome until August 1870, when they were recalled at the start of the Franco-Prussian War. In September 1870, Garibaldi's soldiers finally entered Rome and made it the capital of Italy.

After the successful conclusion of the Italian campaign and the annexation of Savoy and Nice to the territory of France, the Continental foreign policy of Napoleon III entered a calmer period. Expeditions to distant corners of the world and the expansion of the Empire replaced major changes in the map of Europe.

The Emperor's health declined; he gained weight, he began to dye his hair to cover the gray, he walked slowly because of gout, and in 1864, at the military camp of Châlons-en-Champagne, he suffered the first medical crisis from his gallstones, the ailment that killed him nine years later. He was less engaged in governing and less attentive to detail, but still sought opportunities to increase French commerce and prestige globally.

Overseas empire

In 1862, Napoleon III sent troops to Mexico in an effort to establish an allied monarchy in the Americas, with Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria enthroned as Emperor Maximilian I. The Second Mexican Empire faced resistance from the republican government of President Benito Juárez, however. After victory in the American Civil War in 1865, the United States made clear that France would

have to leave. It sent 50,000 troops under General Philip H. Sheridan to the Mexico–United States border and helped resupply Juárez. Napoleon's military was stretched very thin; he had committed 40,000 troops to Mexico, 20,000 to Rome to guard the Pope against the Italians, as well as another 80,000 in restive Algeria. Furthermore, Prussia, having just defeated Austria in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, was an imminent threat. Napoleon realised his predicament and withdrew his

troops from Mexico in 1866. Maximilian was overthrown and executed.

Emperor Maxilian I of Mexico

In Southeast Asia, Napoleon III was more successful in establishing control with one limited military operation at a time. In the Cochinchina Campaign, he took over Cochinchina (the southernmost part of modern Vietnam, including Saigon) in 1862. In 1863, he established a protectorate over Cambodia. Additionally, France had a sphere of influence during the 19th century and early 20th century in Southern China, including a naval base at Kuangchow Bay (Guangzhouwan).

According to information given to Abdón Cifuentes in 1870 the possibility of an intervention in favour of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia against Chile was discussed in Napoleon's Conseil d'État.

In 1870 the French battleship D'Entrecasteaux anchored at Corral drawing suspicions from Cornelio Saavedra of some sort of French interference in the ongoing occupation of Mapuche lands.

A shipment arms was seized by Argentine authorities at Buenos Aires in 1871, reportedly this had been ordered by Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, the so-called King of Araucanía and Patagonia.

At his court

Following the model of the Kings of France and of his uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon III moved his official residence to the Tuileries Palace, where he had a suite of rooms on the ground floor of the south wing between the Seine and the Pavillon de l'Horloge (Clock pavilion), facing the garden.

Dinner at the Tuileries Palace in 1867

The French word tuileries denotes "brickworks" or "tile-making works". The palace was given that name because the neighbourhood in which it had been built in 1564 was previously known for its numerous mason and tiler businesses.

Napoleon III's bedroom was decorated with a talisman from Charlemagne (a symbol of good luck for the Bonaparte family), while his office featured a portrait of Julius Caesar by Ingres and a large map of Paris that he used to show his ideas for the reconstruction of Paris to his prefect of the Seine department, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann.

The Emperor's rooms were overheated and were filled with smoke, as he smoked cigarette after cigarette. The Empress occupied a suite of rooms just above his, highly decorated in the style of

Louis XVI with a pink salon, a green salon and a blue salon.

The court moved with the Emperor and Empress from palace to palace each year following a regular calendar.

At the beginning of May, the Emperor and court moved to the Château de Saint-Cloud for outdoor activities in the park.

In June and July, they moved with selected guests to the Palace of Fontainebleau for walks in the forest and boating on the lake.

In July, the court moved to thermal baths for a health cure, first to Plombières, then to Vichy, and then, after 1856, to the military camp and residence built at Châlons-sur-Marne (nowadays: Châlons-en-Champagne), where Napoleon could take the waters and review military parades and exercises.

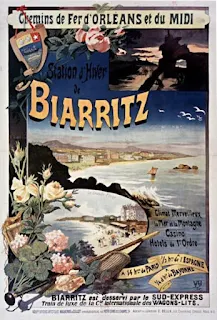

Beginning in 1856, the Emperor and Empress spent each September in Biarritz in the Villa Eugénie, a large villa overlooking the sea. They would walk on the beach or travel to the mountains, and in the evenings they would dance and sing and play cards and take part in other games and amateur theatricals and charades with their guests.

In November, the court moved to the Château de Compiègne for forest excursions, dancing and more games. Famous scientists and artists, such as Louis Pasteur, Gustave Flaubert, Eugène Delacroix

and Giuseppe Verdi, were invited to participate in the festivities at Compiègne.

At the end of the year the Emperor and Court returned to the Tuileries Palace and gave a series of formal receptions and three or four grand balls with six hundred guests early in the new year. Visiting dignitaries and monarchs were frequently invited.

During Carnival, there was a series of very elaborate costume balls on the themes of different countries and different historical periods, for which guests sometimes spent small fortunes on their costumes.

Napoleon III was widely renowned for the memorization of people's names. Not only would the emperor hear the name by ear, he would also write the name down on a paper and study it.

Once the emperor was finished with the time he had spent looking at the name, he would rip and then throw away the paper.

Arts

When Édouard Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe and other avant-garde paintings were rejected by the Paris Salon of 1863, Napoleon III ordered that the works be displayed, so that the public could judge for themselves.

Napoleon III had conservative and traditional taste in art: his favourite painters were Alexandre Cabanel and Franz Xaver Winterhalter, who received major commissions, and whose work was purchased

for state museums.

Empress Eugenie and her ladies in waiting

painting by Franz Xaver Winterhalter

At the same time, he followed public opinion, and he made an important contribution to the French avant-garde.

In 1863, the jury of the Paris Salon, the famous annual showcase of French painting, headed by the ultra-conservative director of the Academy of Fine Arts, Count Émilien de Nieuwerkerke, refused

all submissions by avant-garde artists, including those by Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro and Johan Jongkind. The artists and their friends complained, and the complaints reached Napoleon III.

Following Napoleon's decree, an exhibit of the rejected paintings, called the Salon des Refusés, was held in another part of the Palace of Industry, where the Salon took place. More than a thousand visitors a day came to see now-famous paintings such as Édouard Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe and James McNeill Whistler's Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. '

Napoleon III also began or completed the restoration of several important historic landmarks, carried out for him by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. He restored the flèche, or spire, of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, which had been partially destroyed and desecrated during the French Revolution. In 1855, he completed the restoration, begun in 1845, of the stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle, and in 1862, he declared it a national historical monument. In 1853, he approved and provided funding for Viollet-le-Duc's restoration of the medieval town of Carcassonne.

He also sponsored Viollet-le-Duc's restoration of the Château de Vincennes and the Château de Pierrefonds, In 1862, he closed the prison which had occupied the Abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel since the French Revolution, where many important political prisoners had been held, so it could be restored and opened to the public.

In the country

From the beginning of his reign, Napoleon III launched a series of social reforms aimed at improving the life of the working class. He began with small projects, such as opening up two clinics in Paris for sick and injured workers, a programme of legal assistance to those unable to afford it, as well as subsidies to companies that built low-cost housing for their workers. He outlawed the practice of employers taking possession of or making comments in the work document that every employee was required to carry; negative comments meant that workers were unable to get other jobs.

In 1866, he encouraged the creation of a state insurance fund to help workers or peasants who became disabled and help their widows and families.

To help the working class, Napoleon III offered a prize to anyone who could develop an inexpensive substitute for butter; the prize was won by the French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, who in 1869 patented a product he named oleomargarine, later shortened simply to margarine.

His most important social reform was the 1864 law that gave French workers the right to strike, which had been forbidden since 1810. In 1866, he added to this an "Edict of Tolerance" which gave factory workers the right to organise. He issued a decree regulating the treatment of apprentices and limited

working hours on Sundays and holidays. He removed from the Napoleonic Code the infamous article 1781, which said that the declaration of the employer, even without proof, would be given more weight by the court than the word of the employee.

Women rights

In 1861, through the direct intervention of the Emperor and the Empress Eugénie, Julie-Victoire Daubié became the first woman to receive a baccalauréat diploma. Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie worked to give girls and women greater access to public education. In 1861, through the direct

intervention of the Emperor and the Empress, Julie-Victoire Daubié became the first woman in France to receive the baccalauréat diploma.

In 1862, the first professional school for young women was opened, and Madeleine Brès became the first woman to enroll in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris.

In 1863, he made Victor Duruy, the son of a factory worker and a respected historian, his new Minister of Public Education. Duruy accelerated the pace of the reforms, often coming into conflict with the Catholic Church, which wanted the leading role in education. Despite the opposition of the Church, Duruy opened schools for girls in each commune with more than five hundred residents, a total of eight hundred new schools.

Economics

One of the centerpieces of the economic policy of Napoleon III was the lowering of tariffs and the opening of French markets to imported goods. He had been in Britain in 1846 when Prime Minister Robert Peel had lowered tariffs on imported grains, and he had seen the benefits to British consumers and the British economy. However, he faced bitter opposition from many French industrialists and farmers, who feared British competition. Convinced he was right, he sent his chief economic advisor,

Michel Chevalier, to London to begin discussions, and secretly negotiated a new commercial agreement with Britain, calling for the gradual lowering of tariffs in both countries.

He signed the treaty, without consulting with the Assembly, on 23 January 1860. Four hundred of the top industrialists in France came to Paris to protest, but he refused to yield. Industrial tariffs on such products as steel rails for railways were lowered first; tariffs on grains were not lowered until June 1861. Similar agreements were negotiated with the Netherlands, Italy, and France's other neighbors. France's industries were forced to modernize and become more efficient to compete with the British, as

Napoleon III had intended.

Commerce between the countries surged. By the 1860s, the huge state investment in railways, infrastructure and fiscal policies of Napoleon III had brought dramatic changes to the

French economy and French society.

French people travelled in greater numbers, more often and farther than they had ever travelled before. The opening of the first public school libraries by Napoleon III and the opening by Louis Hachet te of the first bookstores in Napoleon's new train stations led to the wider circulation of books around France.

During the Empire, industrial production increased by 73 percent, growing twice as rapidly as that of the United Kingdom, though its total output remained lower. From 1850 to 1857, the French economy grew at a pace of five percent a year and exports grew by sixty percent between 1855 and 1869.

French agricultural production increased by sixty percent, spurred by new farming techniques taught at the agricultural schools started in each Department by Napoleon III, and new markets opened by the railways. The threat of famine, which for centuries had haunted the French countryside, receded. The last recorded famine in France was in 1855.

In the 1860s, Prussia appeared on the horizon as a new rival to French power in Europe. Its chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, had ambitions for Prussia to lead a unified Germany. In May 1862, Bismarck came to Paris on a diplomatic mission and met Napoleon III for the first time. They had cordial relations. On 30 September 1862, however, in Munich, Bismarck declared, in a famous speech: "It is not by speeches and votes of the majority that the great questions of our period will be settled, as one believed in 1848,

but by iron and blood." Bismarck saw Austria and France as the main obstacles to his ambitions, and he set out to divide and defeat them.

In the winter and spring of 1864, when the German Confederation invaded and occupied the German-speaking provinces of Denmark (Schleswig and Holstein), Napoleon III recognized the threat that a unified Germany would pose to France, and he looked for allies to challenge Germany, without success.

The British government was suspicious that Napoleon wanted to take over Belgium and Luxembourg, felt secure with its powerful navy, and did not want any military engagements on the European continent at the side of the French.

The Russian government was also suspicious of Napoleon, whom it believed had encouraged Polish nationalists to rebel against Russian rule in 1863. Bismarck and Prussia, on the other hand, had offered assistance to Russia to help crush the Polish patriots.

In October 1865, Napoleon had a cordial meeting with Bismarck at Biarritz. They discussed Venetia, Austria's remaining province in Italy. Bismarck told Napoleon that Germany had no secret arrangement to give Venetia to Italy, and Napoleon assured him in turn that France had no secret understanding with

Austria. Bismarck hinted vaguely that, in the event of a war between Austria and Prussia, French neutrality would be rewarded with some sort of territory as a compensation. Napoleon III had Luxembourg in mind.

Bismarck

In 1866, relations between Austria and Prussia worsened and Bismarck demanded the expulsion of Austria from the German Confederation. Napoleon and his foreign minister, Drouyn de Lhuys, expected a long war and an eventual Austrian victory. Napoleon III felt he could extract a price from both Prussia and Austria for French neutrality. On 12 June 1866, France signed a secret treaty with Austria, guaranteeing French neutrality in a Prussian-Austrian war. In exchange, in the event of an Austrian victory, Austria would give Venetia to France and would also create a new independent German state on the Rhine, which would become an ally of France. At the same time, Napoleon proposed a secret treaty with Bismarck, promising that France would remain neutral in a war between Austria and Prussia. In the event of a Prussian victory, France would recognize Prussia's annexation of smaller German states, and France, in exchange, would receive a portion of German territory, the Palatinate region north of Alsace.

Bismarck, rightly confident of success due to the modernization of the Prussian Army, summarily rejected Napoleon's offer.

On 15 June, the Prussian Army invaded Saxony, an ally of Austria. On 2 July, Austria asked Napoleon to arrange an armistice between Italy, which had allied itself with Prussia, and Austria, in exchange

for which France would receive Venetia.

But on 3 July, the Prussian army crushed the Austrian army at the Battle of Königgrätz in Bohemia. The way to Vienna was open for the Prussians, and Austria asked for an armistice. The armistice was signed on 22 July; Prussia annexed the Kingdom of Hanover, the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel, the Duchy of Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt, with a combined population of four million people.

The Austrian defeat was followed by a new crisis in the health of Napoleon III. Marshal Canrobert, who saw him on 28 July, wrote that the Emperor "was pitiful to see. He could barely sit up in his armchair, and his drawn face expressed at the same time moral anguish and physical pain.

Luxembourg

Napoleon III still hoped to receive some compensation from Prussia for French neutrality during the war. His foreign minister, Drouyn, asked Bismarck for the Palatinate region on the Rhine, which belonged to Bavaria, and for the demilitarization of Luxembourg, which was the site of a formidable fortress staffed by a strong Prussian garrison in accordance with international treaties. Napoleon's senior advisor Eugène Rouher increased the demands, asking that Prussia accept the annexation by France of Belgium and of Luxembourg.

Luxembourg had regained its de jure independence in 1839 as a grand duchy. However, it was in personal union with the Netherlands. King William III of the Netherlands, who was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg, desperately needed money and was prepared to sell the Grand Duchy to France. Bismarck swiftly intervened and showed the British ambassador a copy of Napoleon's demands; as a result, he put pressure on William III to refuse to sell Luxembourg to France. France was forced to renounce any claim to Luxembourg in the Treaty of London (1867). Napoleon III gained nothing for his efforts but the demilitarization of the Luxembourg fortress.

Prussia the old enemy

In the autumn of 1867, Napoleon III proposed a form of universal military service similar to the Prussian system to increase the size of the French Army, if needed, to 1 million.

His proposal was opposed by many French officers, such as Marshal Randon, who preferred a smaller, more professional army; he said: "This proposal will only give us recruits; it's soldiers we need."

It was also strongly opposed by the republican opposition in the French parliament, who denounced the proposal as a militarization of French society.

Facing almost certain defeat in the parliament, Napoleon III withdrew the proposal. It was replaced in January 1868 by a much more modest project to create a garde mobile, or reserve force, to support the army.

Napoleon III was overconfident in his military strength and went into war even after he failed to find any allies who would support a war to stop German unification.

Following the defeat of Austria, Napoleon resumed his search for allies against Prussia.

In April 1867, he proposed an alliance, defensive and offensive, with Austria. If Austria joined France in a victorious war against Prussia, Napoleon promised that Austria could form a new confederation with the southern states of Germany and could annex Silesia, while France took for its part the left bank of the Rhine River. But the timing of Napoleon's offer was poorly chosen; Austria was in the process of a major internal reform, creating a new twin monarchy structure with two components, one being the

Empire of Austria and the other being the Kingdom of Hungary.

Napoleon III also made one last attempt to persuade Italy to be his ally against Prussia. Italian King Victor Emmanuel was personally favorable to a better relationship with France, remembering the role that Napoleon III had played in achieving Italian unification, but Italian public opinion was largely hostile to France; on 3 November 1867, French and Papal soldiers had fired upon the Italian patriots

of Garibaldi, when he tried to capture Rome. Napoleon presented a proposed treaty of alliance on 4 June 1869, the anniversary of the joint French-Italian victory at Magenta. The Italians responded by demanding that France withdraw its troops who were protecting the Pope in Rome. Given the opinion of fervent French Catholics, this was a condition Napoleon III could not accept.

While Napoleon III was having no success finding allies, Bismarck signed secret military treaties with the southern German states, who promised to provide troops in the event of a war between Prussia and France.

In 1868, Bismarck signed an accord with Russia that gave Russia liberty of action in the Balkans in exchange for neutrality in the event of a war between France and Prussia. This treaty put additional pressure on Austria, which also had interests in the Balkans, not to ally itself with France.

But most importantly, Prussia promised to support Russia in lifting the restrictions of the Congress of Paris (1856). "Bismarck had bought Tsar Alexander II’s complicity by promising to help restore his naval access to the Black Sea and Mediterranean (cut off by the treaties ending the Crimean War), other powers were less biddable".

Bismarck also reached out to the liberal government of William Gladstone in London, offering to protect the neutrality of Belgium against a French threat. The British Foreign Office under Lord Clarendon mobilized the British fleet, to dissuade France against any aggressive moves against Belgium. In any war between France and Prussia, France would be entirely alone.

In France, patriotic sentiment was also growing. On 8 May 1870, French voters had overwhelmingly supported Napoleon III's program in a national plebiscite.

The Emperor was less popular in Paris and the big cities, but highly popular in the French countryside. Napoleon had named a new foreign minister, Antoine Agenor, the Duke de Gramont, who was hostile to Bismarck. The Emperor was weak and ill, but the more extreme Bonapartists were prepared to show

their strength against the republicans and monarchists in the parliament.

In July 1870, Bismarck found a cause for a war in an old dynastic dispute.

In September 1868, Queen Isabella II of Spain had been overthrown and exiled to France.

The new government of Spain considered several candidates, including Leopold, Prince of Hohenzollern, a cousin of King Wilhelm I of Prussia.

Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany

At the end of 1869, Napoleon III had let it be known to the Prussian king and his Chancellor Bismarck that a Hohenzollern prince on the throne of Spain would not be acceptable to France.

King Wilhelm had no desire to enter into a war against Napoleon III and did not pursue the subject further. At the end of May, however, Bismarck wrote to the father of Leopold, asking him to put pressure on his son to accept the candidacy to be King of Spain. Leopold, solicited by both his father and Bismarck, agreed.

The news of Leopold's candidacy, published 2 July 1870, aroused fury in the French parliament and press. The government was attacked by both the republicans and monarchist opposition, and by the ultra-Bonapartists, for its weakness against Prussia.

On 6 July, Napoleon III held a meeting of his ministers at the château of Saint-Cloud and told them that Prussia must withdraw the Hohenzollern candidacy or there would be a war.

He asked Marshal Leboeuf, the chief of staff of the French army, if the army was prepared for a war against Prussia. Leboeuf responded that the French soldiers had a rifle superior to the Prussian rifle, that the French artillery was commanded by an elite corps of officers, and that the army "would not lack a button on its puttees". He assured the Emperor that the French army could have four hundred thousand men on the Rhine in less than fifteen days.

King Wilhelm I did not want to be seen as the instigator of the war; he had received messages urging restraint from Emperor Alexander II of Russia, Queen Victoria, and the King of the Belgians.

On 10 July, he told Leopold's father that his candidacy should be withdrawn. Leopold resisted the idea, but finally agreed on the 11th, and the withdrawal of the candidacy was announced on the 12th, a diplomatic victory for Napoleon.

On the evening of the 12th, after meeting with the Empress and with his foreign minister, Gramont, he decided to push his success a little further; he would ask King Wilhelm to guarantee the Prussian

government would never again make such a demand for the Spanish throne.

The French Ambassador to Prussia, Count Vincent Benedetti was sent to the German spa resort of Bad Ems, where the Prussian King was staying. Benedetti met with the King on 13 July in the park of the château. The King told him courteously that he agreed fully with the withdrawal of the Hohenzollern candidacy, but that he could not make promises on behalf of the government for the future. He

considered that the matter was closed. As he was instructed by Gramont, Benedetti asked for another meeting with the King to repeat the request, but the King politely, yet firmly, refused. Benedetti returned to Paris and the affair seemed finished.

Count Vincent Benedetti

On 19 July 1870, a declaration of war was sent to the Prussian government.

The Franco-Prussian War

At the outbreak of the war, crowds gathered on the Place de la Bastille, chanting "To Berlin!"

When France entered the war, there were patriotic demonstrations in the streets of Paris, with crowds singing La Marseillaise and chanting "To Berlin! To Berlin!" But Napoleon was melancholic. He told General Lepic that he expected the war to be "long and difficult", and wondered, "Who knows if we'll come back?" He told Marshal Randon that he felt too old for a military campaign.

Despite his declining health, Napoleon decided to go with the army to the front as commander in chief, as he had done during the successful Italian campaign. On 28 July, he departed Saint-Cloud by train for the front. He was accompanied by the 14-year-old Prince Imperial in the uniform of the army, by his military staff, and by a large contingent of chefs and servants in livery. He was pale and visibly in pain. The Empress remained in Paris as the Regent, as she had done on other occasions when the Emperor was out of the country.

The mobilization of the French army was chaotic. Two hundred thousand soldiers converged on the German frontier, along a front of 250 kilometers, choking all the roads and railways for miles. Officers and their respective units were unable to find one another. General Moltke and the German army, having gained experience mobilizing in the war against Austria, were able to efficiently move three armies of 518,000 men to a more concentrated front of just 120 kilometers.

On 2 August, Napoleon and the Prince Imperial accompanied the army as it made a tentative crossing of the German border toward the city of Saarbrücken. The French won a minor skirmish and advanced no further. Napoleon III, very ill, was unable to ride his horse and had to support himself by leaning against a tree. In the meantime, the Germans had assembled a much larger army opposite Alsace and Lorraine than the French had expected or were aware of.

On 4 August 1870, the Germans attacked with overwhelming force against a French division in Alsace at the Battle of Wissembourg (German: Weissenburg), forcing it to retreat. On 5 August, the Germans defeated another French Army at the Battle of Spicheren in Lorraine.

On 6 August, 140,000 Germans attacked 35,000 French soldiers at the Battle of Wörth; the French lost 19,200 soldiers killed, wounded and captured, and were forced to retreat. The French soldiers fought bravely, and French cavalry and infantry attacked the German lines repeatedly, but the Germans had superior logistics, communications, and leadership. The decisive weapon was the new German Krupp

six pound field gun, which was breech-loading, had a steel barrel, longer range, a higher rate of fire, and was more accurate than the bronze muzzle-loading French cannons. The Krupp guns caused terrible casualties in the French ranks.

Defeat

When news of the French defeats reached Paris on 7 August, it was greeted with disbelief and dismay. Prime Minister Ollivier and the army chief of staff, Marshal Edmond Le Boeuf, both resigned. The Empress Eugénie took it upon herself as the Regent to name a new government. She chose General Cousin-Montauban, better known as the Count of Palikao, seventy-four years old and former commander of the French expeditionary force to China, as her new prime minister. The Count of Palikao named Marshal François Achille Bazaine, the commander of the French forces in Lorraine, as the new military commander. Napoleon III proposed returning to Paris, realizing that he was not doing any good for the army.

The Empress, in charge of the government, responded by telegraph, "Don't think of coming back, unless you want to unleash a terrible revolution. They will say you quit the army to flee the danger." The Emperor agreed to remain with the army.

With the Empress directing the country, and Bazaine commanding the army, the Emperor no longer had any real role to play. At the front, the Emperor told Marshal Leboeuf, "we've both been dismissed."

On 18 August 1870, the Battle of Gravelotte, the biggest battle of the war, took place in Lorraine between the Germans and the army of Marshal Bazaine. The Germans suffered 20,000 casualties and the French 12,000, but the Germans emerged as the victors, as Marshal Bazaine's army, with 175,000 soldiers, six divisions of cavalry and five hundred cannons, was trapped inside the fortifications of Metz, unable to move.

Napoleon was at Châlons-sur-Marne with the army of Marshal Patrice de MacMahon. MacMahon, Marshal Bazaine, and the count of Palikao, with the Empress in Paris, all had different ideas of what the army should do next, and the Emperor had to act as a referee. The Emperor and MacMahon proposed moving their army closer to Paris to protect the city, but on 17 August Bazaine telegraphed to the Emperor: "I urge you to renounce this idea, which seems to abandon the Army at Metz... Couldn't you make a powerful diversion toward the Prussian corps, which are already exhausted by so many battles? The Empress shares my opinion." Napoleon III wrote back, "I yield to your opinion."

The Emperor sent the Prince Imperial back to Paris for his safety, and went with the weary army in the direction of Metz. The Emperor, riding in an open carriage, was jeered, sworn at and insulted by demoralized soldiers.

The direction of movement of MacMahon's army was supposed to be secret, but it was published in the French press and thus was quickly known to the German general staff. Moltke, the German commander, ordered two Prussian armies marching toward Paris to turn towards MacMahon's army.